For early Americans, the body offered one of the primary means of experiencing and understanding the natural world. Their bodies were a medium through which to experience nature and communicate that experience. As Ralph Waldo Emerson explains in “Nature”: “Thus is Art, a nature passed through the alembic of man. Thus in art, does nature work through the will of a man filled with the beauty of her first works.”

One example of how nature was experienced through the body can be seen in the writing of Jupiter Hammon. Hammon combines religious teachings and beliefs with sensory experiences of the natural world, particularly in his usage of imagery of the sky, shores, and seas. While these natural images are given religious meaning and significance, they also represent the very real physical world in which Hammon lived. Hammon lived most of his life on Lloyd’s Neck, Long Island, New York, in homes right next to the shore of Lloyd Harbor. This integration of the natural and supernatural reveals how the natural world helped to vivify the theological underpinnings of Hammon’s writings. His reliance on metaphors that evoke the senses as a way of demonstrating religious belief inadvertently reaffirms sensory experience as central to the way he constructed knowledge.

The natural surroundings in which Hammon lived affected not just his choice of poetic imagery, but also his physical body. Thirty years before Hammon’s began publishing his writing, a 1730 letter describes a then nineteen-year-old Hammon’s illness from gout, described in the letter as a “gouty Rumatick Disorder.” At this time, Lloyd’s Neck had a large deer population; it is entirely likely that Hammon’s diet consisted largely of deer meat, as well as seafood from Lloyd Harbor. Such a diet could lead to or exacerbate Hammon’s gout. The doctor writing the letter goes on to prescribe a treatment plan for Hammon, including purges, bleedings, and taking mixtures of various herbal remedies (“some Diet Drink made to the equal of Horse Raddish Roots the bark of elder Root Pine Budds or the second bark wood or Toad sorrel”). The natural world was both the cause of Hammon’s bodily illness and its remedy.

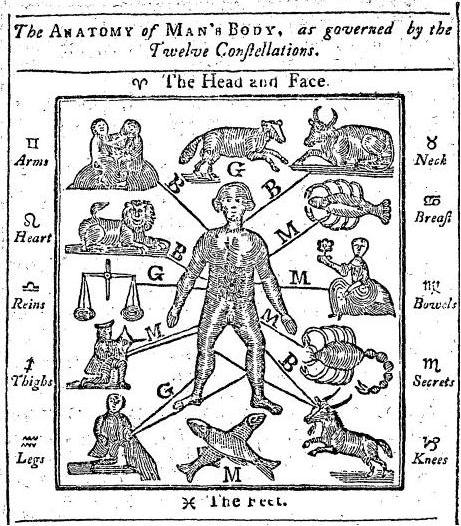

As evidenced by Hammon’s life and work, along with considering bodies as a valuable way of experiencing the natural world, European Americans expressed great concern about how the new American nature would affect their bodies including fears that the American environment and climate would degrade and corrupt their bodies. The environment and climate was also believed by many to be responsible for differences in skin color. These concerns are based in a belief in humoral theory, in which, according to Susan Scott Parrish, “Nature was thus not only understood as a potential stock of resources or a plot of property or as the new location of an old drama between God and humanity; it was also breathed in, drunk, eaten, absorbed under the skin, and incorporated into one’s faculties” (78). Early Americans were very much concerned with how the physical environment acted or impinged on their minds and bodies; for them, nature was not merely an inert backdrop. Such a discussion of humoral theory seems to presage the current focus on trans-corporeality and concerns about toxins and chemicals entering the body.

Numerous early American literary texts reflect this concern with humoral theory: Cotton Mather’s essay “The Negro Christianized” features an environmental explanation to account for variations in skin color of humans, Richard Allen’s and Absalom Jones’s Narrative contains descriptions of bleeding patients as a way of treating yellow fever, as well as reports from doctors that black people were immune to the fever, J. Hector St. John de Crevecoeur’s Letters from an American Farmer shows how the mild, humid climate of Charles Town leads to human degradation and depravity, and Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia offers a refutation of European naturalists’ characterization of America as a land that causes degeneration in both humans and nonhuman animals.

Allen, Richard, and Absalom Jones. “A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the Year 1793.”

Crevecoeur, J. Hector St. John de. Letters from an American Farmer

Jefferson, Thomas. Notes on the States of Virginia

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “Nature.”

Hammon, Jupiter. "An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ With Penetential Cries", "An Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley", "A Poem for Children, With Thoughts on Death", "A Dialogue, Intitled, The Kind Master and the Dutiful Servant".

Mather, Cotton. “The Negro Christianized”

Alaimo, Stacy. Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 201. Print.

Chaplin, Joyce E. Subject Matter: Technology, the Body, and Science on the Anglo-American Frontier, 1500-1676. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2001.Print.

Egan. Jim. Authorizing Experience: Refigurations of the Body Politic in Seventeenth-Century New England Writing. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1999. Print.

Finseth, Ian. Shades of Green: Visions of Nature in the Literature of American Slavery, 1770-1860. Athens: Georgia UP, 2009. Print

Lindman, Janet Moore, and Michele Lise Tarter, Eds. A Centre of Wonders: The Body in Early America. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2001. Print.

Parrish, Susan Scott. American Curiosity: Cultures of Natural History in the Colonial British Atlantic World. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P. 2006. Print.

Wheeler, Roxann. The Complexion of Race: Categories of Difference in Eighteenth-Century British Culture. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 2000. Print.